Notebook Export

Bad Blood

John Carreyrou

Prologue

Highlight(yellow) - Location 78

Tim Kemp had good news for his team. The former IBM executive was in charge of bioinformatics at Theranos, a startup with a cutting-edge blood-testing system. The company had just completed its first big live demonstration for a pharmaceutical company. Elizabeth Holmes, Theranos’s twenty-two-year-old founder, had flown to Switzerland and shown off the system’s capabilities to executives at Novartis, the European drug giant. “Elizabeth called me this morning,” Kemp wrote in an email to his fifteen-person team. “She expressed her thanks and said that, ‘it was perfect!’ She specifically asked me to thank you and let you all know her appreciation. She additionally mentioned that Novartis was so impressed that they have asked for a proposal and have expressed interest in a financial arrangement for a project. We did what we came to do!” This was a pivotal moment for Theranos. The three-year-old startup had progressed from an ambitious idea Holmes had dreamed up in her Stanford dorm room to an actual product a huge multinational corporation was interested in using.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 93

She might be young, but she was surrounded by an all-star cast. The chairman of her board was Donald L. Lucas, the venture capitalist who had groomed billionaire software entrepreneur Larry Ellison and helped him take Oracle Corporation public in the mid-1980s. Lucas and Ellison had both put some of their own money into Theranos. Another board member with a sterling reputation was Channing Robertson, the associate dean of Stanford’s School of Engineering. Robertson was one of the stars of the Stanford faculty. His expert testimony about the addictive properties of cigarettes had forced the tobacco industry to enter into a landmark $6.5 billion settlement with the state of Minnesota in the late 1990s. Based on the few interactions Mosley had had with him, it was clear Robertson thought the world of Elizabeth. Theranos also had a strong management team. Kemp had spent thirty years at IBM. Diane Parks, Theranos’s chief commercial officer, had twenty-five years of experience at pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies. John Howard, the senior vice president for products, had overseen Panasonic’s chip-making subsidiary. It wasn’t often that you found executives of that caliber at a small startup.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 131

Well, there was a reason it always seemed to work, Shaunak said. The image on the computer screen showing the blood flowing through the cartridge and settling into the little wells was real. But you never knew whether you were going to get a result or not. So they’d recorded a result from one of the times it worked. It was that recorded result that was displayed at the end of each demo.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 163

Mosley was dubious given what he now knew. He brought up what Shaunak had told him about the investor demos. They should stop doing them if they weren’t completely real, he said. “We’ve been fooling investors. We can’t keep doing that.” Elizabeth’s expression suddenly changed. Her cheerful demeanor of just moments ago vanished and gave way to a mask of hostility. It was like a switch had been flipped. She leveled a cold stare at her chief financial officer. “Henry, you’re not a team player,” she said in an icy tone. “I think you should leave right now.” There was no mistaking what had just happened. Elizabeth wasn’t merely asking him to get out of her office. She was telling him to leave the company—immediately. Mosley had just been fired.

1. A Purposeful Life

Highlight(yellow) - Location 240

Over winter break of her freshman year, Elizabeth returned to Houston to celebrate the holidays with her parents and the Dietzes, who flew down from Indianapolis. She’d only been in college for a few months, but she was already entertaining thoughts of dropping out. During Christmas dinner, her father floated a paper airplane toward her end of the table with the letters “P.H.D.” written on its wings. Elizabeth’s response was blunt, according to a family member in attendance: “No, Dad, I’m not interested in getting a Ph.D., I want to make money.”

Highlight(yellow) - Location 283

Not everyone bought the pitch. One morning in July 2004, Elizabeth met with MedVenture Associates, a venture capital firm that specialized in medical technology investments. Sitting across a conference room table from the firm’s five partners, she spoke quickly and in grand terms about the potential her technology had to change mankind. But when the MedVenture partners asked for more specifics about her microchip system and how it would differ from one that had already been developed and commercialized by a company called Abaxis, she got visibly flustered and the meeting grew tense. Unable to answer the partners’ probing technical questions, she got up after about an hour and left in a huff. MedVenture Associates wasn’t the only venture capital firm to turn down the nineteen-year-old college dropout. But that didn’t stop Elizabeth from raising a total of nearly $6 million by the end of 2004 from a grab bag of investors.

2. The Gluebot

Highlight(yellow) - Location 337

Her obsession with miniaturization extended to the cartridge. She wanted it to fit in the palm of a hand, further complicating Ed’s task. He and his team spent months reengineering it, but they never reached a point where they could reliably reproduce the same test results from the same blood samples. The quantity of blood they were allowed to work with was so small that it had to be diluted with a saline solution to create more volume. That made what would otherwise have been relatively routine chemistry work a lot more challenging. Adding another level of complexity, blood and saline weren’t the only fluids that had to flow through the cartridge. The reactions that occurred when the blood reached the little wells required chemicals known as reagents. Those were stored in separate chambers. All these fluids needed to flow through the cartridge in a meticulously choreographed sequence, so the cartridge contained little valves that opened and shut at precise intervals. Ed and his engineers tinkered with the design and the timing of the valves and the speed at which the various fluids were pumped through the cartridge. Another problem was preventing all those fluids from leaking and contaminating one another. They tried changing the shape, length, and orientation of the tiny channels in the cartridge to minimize the contamination. They ran countless tests with food coloring to see where the different colors went and where the contamination occurred. It was a complicated, interconnected system compressed into a small space. One of Ed’s engineers had an analogy for it: it was like a web of rubber bands. Pulling on one would inevitably stretch several of the others. Each cartridge cost upward of two hundred dollars to make and could only be used once. They were testing hundreds of them a week. Elizabeth had purchased a $2 million automated packaging line in anticipation of the day they could start shipping them, but that day seemed far off. Having already blown through its first $6 million, Theranos had raised another $9 million in a second funding round to replenish its coffers.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 388

It was hard to know how much Elizabeth’s approach to running Theranos was her own and how much she was channeling Ellison, Lucas, or Sunny,

Highlight(yellow) - Location 398

Sunny picked them up from the office in his Porsche and drove them to the airport. It was the first time Ed met him in person. The extent of their age gap suddenly became apparent. Sunny looked to be in his early forties, nearly twenty years older than Elizabeth. There was also a cold, businesslike dynamic to their relationship. When they parted at the airport, Sunny didn’t say “Goodbye” or “Have a nice trip.” Instead, he barked, “Now go make some money!”

3. Apple Envy

Highlight(yellow) - Location 510

To anyone who spent time with Elizabeth, it was clear that she worshipped Jobs and Apple. She liked to call Theranos’s blood-testing system “the iPod of health care” and predicted that, like Apple’s ubiquitous products, it would someday be in every household in the country.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 528

Ana felt that Elizabeth could use a makeover herself. The way she dressed was decidedly unfashionable. She wore wide gray pantsuits and Christmas sweaters that made her look like a frumpy accountant. People in her entourage like Channing Robertson and Don Lucas were beginning to compare her to Steve Jobs. If so, she should dress the part, she told her. Elizabeth took the suggestion to heart. From that point on, she came to work in a black turtleneck and black slacks most days.

4. Goodbye East Paly

Highlight(yellow) - Location 721

There was one case in particular that Matt regretted helping her with: that of Henry Mosley, the former chief financial officer. After Elizabeth fired Mosley, Matt had stumbled across inappropriate sexual material on his work laptop as he was transferring its files to a central server for safekeeping. When Elizabeth found out about it, she used it to claim it was the cause of Mosley’s termination and to deny him stock options. Matt had reported to Mosley until he left and thought he’d done an excellent job of helping Elizabeth raise money for Theranos. He clearly shouldn’t have browsed porn on a work-issued laptop, but Matt didn’t think it was a capital offense that merited blackmailing him. And besides, it had been found after the fact. Saying it was the reason Mosley was fired simply wasn’t true. The way John Howard was treated also bothered him. When Matt reviewed all the evidence assembled for the Michael O’Connell lawsuit, he didn’t see anything proving that Howard had done anything wrong. He’d had contact with O’Connell but he’d declined to join his company. Yet Elizabeth insisted on connecting the dots a certain way and suing him too, even though Howard had been one of the first people to help her when she dropped out of Stanford, letting her use the basement of his house in Saratoga for experiments in the company’s early days. (Theranos later dropped the case against its three ex-employees when O’Connell agreed to sign his patent over to the company.)

Highlight(yellow) - Location 840

After some discussion, the four men reached a consensus: they would remove Elizabeth as CEO. She had proven herself too young and inexperienced for the job. Tom Brodeen would step in to lead the company for a temporary period until a more permanent replacement could be found. They called in Elizabeth to confront her with what they had learned and inform her of their decision. But then something extraordinary happened. Over the course of the next two hours, Elizabeth convinced them to change their minds. She told them she recognized there were issues with her management and promised to change. She would be more transparent and responsive going forward. It wouldn’t happen again. Brodeen wasn’t exactly dying to come out of retirement to run a startup in a field in which he had no expertise, so he took a neutral stance and watched as Elizabeth used just the right mix of contrition and charm to gradually win back his three board colleagues. It was an impressive performance, he thought. A much older and more experienced CEO skilled in the art of corporate infighting would have been hard-pressed to turn the situation around like she had. He was reminded of an old saying: “When you strike at the king, you must kill him.” Todd Surdey and Michael Esquivel had struck at the king, or rather the queen. But she’d survived.

6. Sunny

Highlight(yellow) - Location 1161

Sunny’s expertise was software and that was where he was supposed to add value at Theranos. In one of the first company meetings he attended, he bragged that he’d written a million lines of code. Some employees thought that was preposterous. Sunny had worked at Microsoft, where teams of software engineers had written the Windows operating system at the rate of one thousand lines of code per year of development. Even if you assumed Sunny was twenty times faster than the Windows developers, it would still have taken him fifty years to do what he claimed.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 1202

Earlier that year, Pfizer had informed Theranos that it was ending their collaboration because it was underwhelmed by the results of the Tennessee validation study. Elizabeth had tried to put the best spin she could on the fifteen-month study in a twenty-six-page report she’d sent to the New York pharmaceutical giant, but the report had betrayed too many glaring inconsistencies. The study had failed to show any clear link between drops in the patients’ protein levels and the administration of the antitumor drugs. And the report had copped to some of the same snafus Chelsea was now witnessing in Belgium, such as mechanical failures and wireless transmission errors. It had blamed the latter on “dense foliage, metal roofs, and poor signal quality due to remote location.” Two of the Tennessee patients had called the Theranos offices in Palo Alto to complain that the readers wouldn’t start because of temperature issues. “The solution,” according to the report, had been to ask the patients to move the readers “away from A/C units and possible air currents.” One patient had put the device in his RV and the other in a “very hot room” and the temperature extremes had “affected the readers’ ability to maintain desired temperature,” the report said.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 1214

Elizabeth and Sunny’s attention had shifted from Europe to another part of the globe: Mexico. A swine flu epidemic had been raging there since the spring and Elizabeth thought it offered a great opportunity to showcase the Edison. The person who had planted that germ in her mind was Seth Michelson, Theranos’s chief scientific officer. Seth was a math whiz who’d once worked in the flight simulator lab at NASA. His specialty was biomathematics, the use of mathematical models to help understand phenomena in biology. He was in charge of the predictive modeling efforts at Theranos and was Daniel Young’s boss. Seth called to mind Doc Brown from the 1985 Michael J. Fox movie Back to the Future. He didn’t have Doc’s crazy white hair, but he sported a huge, frizzy gray beard that gave him a similar mad scientist look. Though in his late fifties, he still said “dude” a lot and became really animated when he was explaining scientific concepts. Seth had told Elizabeth about a math model called SEIR (the letters stood for Susceptible, Exposed, Infected, and Resolved) that he thought could be adapted to predict where the swine flu virus would spread next. For it to work, Theranos would need to test recently infected patients and input their blood-test results into the model. That meant getting the Edison readers and cartridges to Mexico. Elizabeth envisioned putting them in the beds of pickup trucks and driving them to the Mexican villages on the front lines of the outbreak. Chelsea was fluent in Spanish, so it was decided that she would head down to Mexico with Sunny. Getting authorization to use an experimental medical device in a foreign country is usually no easy thing, but Elizabeth was able to leverage the family connections of a wealthy Mexican student at Stanford.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 1306

Chelsea also worried about Elizabeth. In her relentless drive to be a successful startup founder, she had built a bubble around herself that was cutting her off from reality. And the only person she was letting inside was a terrible influence. How could her friend not see that?

7. Dr. J

Highlight(yellow) - Location 1337

In January 2010, Theranos had approached Walgreens with an email stating that it had developed small devices capable of running any blood test from a few drops pricked from a finger in real time and for less than half the cost of traditional laboratories. Two months later, Elizabeth and Sunny traveled to Walgreens’s headquarters in the Chicago suburb of Deerfield, Illinois, and gave a presentation to a group of Walgreens executives. Dr. J, who flew up from Pennsylvania for the meeting, instantly recognized the potential of the Theranos technology. Bringing the startup’s machines inside Walgreens stores could open up a big new revenue stream for the retailer and be the game changer it had been looking for, he believed. It wasn’t just the business proposition that appealed to Dr. J. A health nut who carefully watched his diet, rarely drank alcohol, and was fanatical about getting a swim in every day, he was passionate about empowering people to live healthier lives. The picture Elizabeth presented at the meeting of making blood tests less painful and more widely available so they could become an early warning system against disease deeply resonated with him. That evening, he could barely contain his excitement over dinner at a wine bar with two Walgreens colleagues who weren’t privy to the secret discussions with Theranos. After asking them to keep what he was about to tell them confidential, he revealed in a hushed tone that he’d found a company he was convinced would change the face of the pharmacy industry. “Imagine detecting breast cancer before the mammogram,” he told his enraptured colleagues, pausing for effect.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 1368

“I’m so excited that we’re doing this!” Dr. J then exclaimed. He was referring to a pilot project the companies had agreed to. It would involve placing Theranos’s readers in thirty to ninety Walgreens stores no later than the middle of 2011. The stores’ customers would be able to get their blood tested with just a prick of the finger and receive their results in under an hour. A preliminary contract had already been signed, under which Walgreens had committed to prepurchase up to $50 million worth of Theranos cartridges and to loan the startup an additional $25 million. If all went well with the pilot, the companies would aim to expand their partnership nationwide. It was unusual for Walgreens to move this quickly. Opportunities the innovation team identified usually got waylaid in internal committees and slowed down by the retailer’s giant bureaucracy. Dr. J had managed to fast-track this one by going straight to Wade Miquelon, Walgreens’s chief financial officer, and getting him behind the project. Miquelon was due to fly in that evening and join them at the next day’s session. About half an hour into discussions centering on the pilot, Hunter asked where the bathroom was. Elizabeth and Sunny visibly stiffened. Security was paramount, they said, and anyone who left the conference room would have to be escorted. Sunny accompanied Hunter to the bathroom, waited for him outside the bathroom door, and then walked him back to the conference room. It seemed to Hunter unnecessary and strangely paranoid. On his way back from the bathroom, he scanned the office for a laboratory but didn’t see anything that looked like one. That’s because it was downstairs, he was told. Hunter said he hoped to see it at some point during the visit, to which Elizabeth responded, “Yes, if we have time.” Theranos had told Walgreens it had a commercially ready laboratory and had provided it with a list of 192 different blood tests it said its proprietary devices could handle. In reality, although there was a lab downstairs, it was just an R&D lab where Gary Frenzel and his team of biochemists conducted their research. Moreover, half of the tests on the list couldn’t be performed as chemiluminescent immunoassays, the testing technique the Edison system relied on. They required different testing methods beyond the Edison’s scope. The meeting resumed and stretched into the middle of the afternoon, at which point Elizabeth suggested they grab an early dinner in town. As they got up from their chairs, Hunter asked again to see the lab. Elizabeth tapped Dr. J on the shoulder and motioned for him to follow her outside the conference room. He returned moments later and told Hunter it wasn’t going to happen. Elizabeth wasn’t willing to show them the lab yet, he said.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 1397

and the green kale shakes she sipped on all day, Elizabeth was going to great lengths to emulate Steve Jobs, but she didn’t seem to have a solid understanding of what distinguished different types of blood tests. Theranos had also failed to deliver on his two basic requests: to let him see its lab and to demonstrate a live vitamin D test on its device. Hunter’s plan had been to have Theranos test his and Dr. J’s blood, then get retested at Stanford Hospital that evening and compare the results. He’d even arranged for a pathologist to be on standby at the hospital to write the order and draw their blood. But Elizabeth claimed she’d been given too little notice even though he’d made the request two weeks ago.

Bookmark - Location 1412

Highlight(yellow) - Location 1422

Hunter, who was now working for Walgreens full-time as an onsite consultant for the innovation team, didn’t take part in the meeting. But when he heard that several Walgreens executives had had their blood tested, he figured this was an opportunity to finally see how the technology performed. He told himself to follow up with Elizabeth about the test results next time they talked. In a report he’d put together after the Palo Alto visit, Hunter had warned that Theranos might be “overselling or overstating…where they are at scientifically with the cartridges/devices.” He’d also recommended that Walgreens embed someone at Theranos through the pilot’s launch and had volunteered one of his Colaborate colleagues, a petite British woman by the name of June Smart who’d recently completed a stint administering Stanford’s labs, for the assignment. Theranos had rejected the idea. Hunter asked about the blood-test results a few days later on the weekly video conference call the companies were using as their primary mode of communication. Elizabeth responded that Theranos could only release the results to a doctor. Dr. J, who was dialed in from Conshohocken, reminded everyone that he was a trained physician, so why didn’t Theranos go ahead and send him the results? They agreed that Sunny would follow up separately with him. A month passed and still no results. Hunter’s patience was wearing thin. During that week’s call, the two sides discussed a sudden change Theranos had made to its regulatory strategy. It had initially represented that its blood tests would qualify as “waived” under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments, the 1988 federal law that governed laboratories. CLIA-waived tests usually involved simple laboratory procedures that the Food and Drug Administration had cleared for home use. Now, Theranos was changing its tune and saying the tests it would be offering in Walgreens stores were “laboratory-developed tests.” It was a big difference: laboratory-developed tests lay in a gray zone between the FDA and another federal health regulator, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS, as the latter agency was known, exercised oversight of clinical laboratories under CLIA, while the FDA regulated the diagnostic equipment that laboratories bought and used for their testing. But no one closely regulated tests that labs fashioned with their own methods. Elizabeth and Sunny had a testy exchange with Hunter over the significance of the change. They maintained that all the big laboratory companies mostly used laboratory-developed tests, which Hunter knew not to be true. To Hunter, the switch made it all the more important to check the accuracy of Theranos’s tests. He suggested doing a fifty-patient study in which they would compare Theranos results to ones from Stanford Hospital. He’d done work with Stanford and knew people there; it would be easy to arrange. On the computer screen, Hunter noticed an immediate change in Elizabeth’s body language. She became visibly guarded and defensive. “No, I don’t think we want to do that at this time,” she said, quickly changing the subject to other items on the call’s agenda. After they hung up, Hunter took aside Renaat Van den Hooff, who was in charge of the pilot on the Walgreens side, and told him something just wasn’t right. The red flags were piling up. First, Elizabeth had denied him access to their lab. Then she’d rejected his proposal to embed someone with them in Palo Alto. And now she was refusing to do a simple comparison study. To top it all off, Theranos had drawn the blood of the president of Walgreens’s pharmacy business, one of the company’s most senior executives, and failed to give him a test result! Van den Hooff listened with a pained look on his face. “We can’t not pursue this,” he said. “We can’t risk a scenario where CVS has a deal with them in six months and it ends up being real.”

Highlight(yellow) - Location 1455

Hunter pleaded with Van den Hooff to at least let him peek inside the one black-and-white reader Theranos had left with them after the Project Beta kickoff party. He was dying to tear the strips of security tape off its case and crack it open. Theranos had sent them some test kits for it, but they were for obscure blood tests like a “flu susceptibility” panel that no other lab he knew of offered. It was therefore impossible to compare their results to anything. How convenient, Hunter had noted. Moreover, the kits were expired. Van den Hooff said no. In addition to signing confidentiality agreements, they’d been sternly warned not to tamper with the reader. The contract the companies had signed stated that Walgreens agreed “not to disassemble or otherwise reverse engineer the Devices or any component thereof.” Trying to contain his frustration, Hunter made one last request. Theranos always invoked two things as proof that its technology had been vetted. The first was the clinical trial work it did for pharmaceutical companies. Documents it gave Walgreens stated that the Theranos system had been “comprehensively validated over the last seven years by ten of the largest fifteen pharma companies.” The second was a review of its technology Dr. J had supposedly commissioned from Johns Hopkins University’s medical school. Hunter had placed calls to pharmaceutical companies and hadn’t been able to get anyone on the phone to confirm what Theranos was claiming, though that was hardly proof of anything. He now asked Van den Hooff to show him the Johns Hopkins review. After some hesitation, Van den Hooff reluctantly handed him a two-page document. When Hunter was done reading it, he almost laughed. It was a letter dated April 27, 2010, summarizing a meeting Elizabeth and Sunny had had with Dr. J and five university representatives on the Hopkins campus in Baltimore. It stated that they had shown the Hopkins team “proprietary data on test performance” and that Hopkins had deemed the technology “novel and sound.” But it also made clear that the university had conducted no independent verification of its own. In fact, the letter included a disclaimer at the bottom of the second page: “The materials provided in no way signify an endorsement by Johns Hopkins Medicine to any product or service.”

Highlight(yellow) - Location 1495

Before long, Safeway too signed a deal with Theranos. Under the agreement, it loaned the startup $30 million and pledged to undertake a massive renovation of its stores to make room for sleek new clinics where customers would have their blood tested on the Theranos devices.

8. The miniLab

Highlight(yellow) - Location 1547

Elizabeth christened the machine she assigned them to build the “miniLab.” As its name suggested, her overarching concern was its size: she still nurtured the vision of someday putting it in people’s homes and wanted something that could fit on a desk or a shelf. This posed engineering challenges because, in order to run all the tests she wanted, the miniLab would need to have many more components than the Edison. In addition to the Edison’s photomultiplier tube, the new device would need to cram three other laboratory instruments in one small space: a spectrophotometer, a cytometer, and an isothermal amplifier. None of these were new inventions. The first commercial spectrophotometer was developed in 1941 by the American chemist Arnold Beckman, founder of the lab equipment maker Beckman Coulter. It works by beaming rays of colored light through a blood sample and measuring how much of the light the sample absorbs. The concentration of a molecule in the blood is then inferred from the level of light absorption. Spectrophotometers are used to measure substances like cholesterol, glucose, and hemoglobin. Cytometry, a way of counting blood cells, was invented in the nineteenth century. It’s used to diagnose anemia and blood cancers, among other disorders. Laboratories all over the world had been using these instruments for decades. In other words, Theranos wasn’t pioneering any new ways to test blood. Rather, the miniLab’s value would lie in the miniaturization of existing lab technology. While that might not amount to groundbreaking science, it made sense in the context of Elizabeth’s vision of taking blood testing out of central laboratories and bringing it to drugstores, supermarkets, and, eventually, people’s homes.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 1559

To be sure, there were already portable blood analyzers on the market. One of them, a device that looked like a small ATM called the Piccolo Xpress, could perform thirty-one different blood tests and produce results in as little as twelve minutes. It required only three or four drops of blood for a panel of a half dozen commonly ordered tests. However, neither the Piccolo nor other existing portable analyzers could do the entire range of laboratory tests. In Elizabeth’s mind, that was going to be the miniLab’s selling point.

Highlight(pink) - Location 1573

Like most people, Greg had been taken aback by Elizabeth’s deep voice when he’d first met her. He soon began to suspect it was affected. One evening, as they wrapped up a meeting in her office shortly after he joined the company, she lapsed into a more natural-sounding young woman’s voice. “I’m really glad you’re here,” she told him as she got up from her chair, her pitch several octaves higher than usual. In her excitement, she seemed to have momentarily forgotten to turn on the baritone. When Greg thought about it, there was a certain logic to her act: Silicon Valley was overwhelmingly a man’s world. The VCs were all male and he couldn’t think of any prominent female startup founder. At some point, she must have decided the deep voice was necessary to get people’s attention and be taken seriously.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 1628

A month or two after Jobs’s death, some of Greg’s colleagues in the engineering department began to notice that Elizabeth was borrowing behaviors and management techniques described in Walter Isaacson’s biography of the late Apple founder. They were all reading the book too and could pinpoint which chapter she was on based on which period of Jobs’s career she was impersonating. Elizabeth even gave the miniLab a Jobs-inspired code name: the 4S. It was a reference to the iPhone 4S, which Apple had coincidentally unveiled the day before Jobs passed away.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 1684

Part of the problem was that Elizabeth and Sunny seemed unable, or unwilling, to distinguish between a prototype and a finished product. The miniLab Greg was helping build was a prototype, nothing more. It needed to be tested thoroughly and fine-tuned, which would require time. A lot of time. Most companies went through three cycles of prototyping before they went to market with a product. But Sunny was already placing orders for components to build one hundred miniLabs, based on a first, untested prototype. It was as if Boeing built one plane and, without doing a single flight test, told airline passengers, “Hop aboard.”

9. The Wellness Play

Highlight(yellow) - Location 1759

He’d ordered the remodeling of more than half of Safeway’s seventeen hundred stores to make room for upscale clinics with deluxe carpeting, custom wood cabinetry, granite countertops, and flat-screen TVs. Per Theranos’s instructions, they were to be called wellness centers and had to look “better than a spa.” Although Safeway was shouldering the entire cost of the $350 million renovation on its own, Burd expected it to more than pay for itself once the new clinics started offering the startup’s novel blood tests.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 1766

There had been quite a few delays since the companies had first agreed to do business together. At one point, Elizabeth told Burd that the earthquake that struck eastern Japan in March 2011 was interfering with Theranos’s ability to produce the cartridges for its devices. Some Safeway executives found the excuse far-fetched, but Burd accepted it at face value. He was starry-eyed about the young Stanford dropout and her revolutionary technology, which fit so perfectly with his passion for preventive health care.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 1792

Bradley had worked with a lot of sophisticated medical technologies in the army, so he was curious to see the Theranos system in action. However, he was surprised to learn that Theranos wasn’t planning on putting any of its devices in the Pleasanton clinic. Instead, it had stationed two phlebotomists there to draw blood, and the samples they collected were couriered across San Francisco Bay to Palo Alto for testing. He also noticed that the phlebotomists were drawing blood from every employee twice, once with a lancet applied to the index finger and a second time the old-fashioned way with a hypodermic needle inserted in the arm. Why the need for venipunctures—the medical term for needle draws—if the Theranos finger-stick technology was fully developed and ready to be rolled out to consumers, he wondered. Bradley’s suspicions were further aroused by the amount of time it took to get results back. His understanding had been that the tests were supposed to be quasi-instantaneous, but some Safeway employees were having to wait as long as two weeks to receive their results. And not every test was performed by Theranos itself. Even though the startup had never said anything about outsourcing some of the testing, Bradley discovered that it was farming out some tests to a big reference laboratory in Salt Lake City called ARUP. What really set off Bradley’s alarm bells, though, was when some otherwise healthy employees started coming to him with concerns about abnormal test results. As a precaution, he sent them to get retested at a Quest or LabCorp location. Each time, the new set of tests came back normal, suggesting the Theranos results were off. Then one day, a senior Safeway executive got his PSA result back. The acronym stands for “prostate-specific antigen,” which is a protein produced by cells in the prostate gland. The higher the protein’s concentration in a man’s blood, the likelier he is to have prostate cancer. The senior Safeway executive’s result was very elevated, indicating he almost certainly had prostate cancer. But Bradley was skeptical. As he had done with the other employees, he sent his worried colleague to get retested at another lab and, lo and behold, that result came back normal too. Bradley put together a detailed analysis of the discrepancies. Some of the differences between the Theranos values and the values from the other labs were disturbingly large. When the Theranos values did match those of the other labs, they tended to be for tests performed by ARUP. Bradley shared his concerns with Renda and with Brad Wolfsen, the president of Safeway Health. Her faith already shaken by the delays of the past two years, Renda encouraged him to talk to Burd about them, which Bradley did. But Burd politely brushed him off, assuring the ex–army doctor that the Theranos technology had been vetted and was sound.

10. “Who Is LTC Shoemaker?”

Highlight(yellow) - Location 1959

The document explained that Theranos’s devices were merely remote sample-processing units. The real work of blood analysis would take place in the company’s lab in Palo Alto, where computers would analyze the data the devices transmitted to it and qualified laboratory personnel would review and interpret the results. Hence only the Palo Alto lab needed to be certified. The devices themselves were akin to “dumb” fax machines and exempt from regulatory oversight. There was a second wrinkle Shoemaker found equally hard to swallow: Theranos maintained that the blood tests its devices performed were laboratory-developed tests and therefore beyond the FDA’s purview. The Theranos position then was that a CLIA certificate for its Palo Alto lab was sufficient for it to deploy and use its devices anywhere.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 1985

Hojvat forwarded his query to five of her colleagues, including Alberto Gutierrez, the director of the FDA’s Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health. Gutierrez, who had a Ph.D. in chemistry from Princeton, happened to have spent a not insignificant portion of his twenty-year career at the agency pondering the question of laboratory-developed tests. The FDA had long considered it within its power to regulate LDTs, as laboratory-developed tests were known. However, in practice, it had not done so because back in 1976, when the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act was amended to expand the agency’s authority from drugs to medical devices, LDTs weren’t common. They were only made by local laboratories occasionally when an unusual medical case required it. That changed in the 1990s when laboratories started to make more complex tests for mass use, including genetic tests. By the FDA’s own reckoning, scores of flawed and unreliable tests had since been marketed for conditions ranging from whooping cough and Lyme disease to various types of cancers, resulting in untold harm to patients. There was a growing consensus within the agency that it needed to start policing this part of the lab business, and the biggest proponent of that view was Gutierrez. When he saw the email Hojvat forwarded to him from Shoemaker, Gutierrez shook his head in disbelief. The approach it described was exactly the type of regulatory end run around the FDA that he wanted to put a stop to. Gutierrez’s view that it was the FDA, not the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, that should regulate LDTs did not mean he didn’t get along with his colleagues at CMS. To the contrary, they had a good working relationship and often communicated across agency lines to try to bridge the regulatory gap spawned by outdated statutes. Gutierrez forwarded the Shoemaker email to Judith Yost and Penny Keller, two members of CMS’s lab-oversight division, adding a note at the top: How about this one!!! Would CMS consider this an LDT? I have a hard time seeing that we would exercise enforcement discretion on this one. Alberto

Highlight(yellow) - Location 2083

The limited experiment agreed upon fell short of the more ambitious live field trial Mattis had had in mind. Theranos’s blood tests would not be used to inform the treatment of wounded soldiers. They would only be performed on leftover samples after the fact to see if their results matched the army’s regular testing methods. But it was something. Earlier in his career, Shoemaker had spent five years overseeing the development of diagnostic tests for biological threat agents and he would have given his left arm to get access to anonymized samples from service members in theater. The data generated from such testing could be very useful in supporting applications to the FDA. Yet, over the ensuing months, Theranos inexplicably failed to take advantage of the opportunity it was given. When General Mattis retired from the military in March 2013, the study using leftover de-identified samples hadn’t begun. When Colonel Edgar took on a new assignment as commander of the Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases a few months later, it still hadn’t started. Theranos just couldn’t seem to get its act together.

11. Lighting a Fuisz

Highlight(yellow) - Location 2136

DAVID BOIES’S LEGEND preceded him. He had risen to national prominence in the 1990s when the Justice Department hired him to handle its antitrust suit against Microsoft. On his way to a resounding courtroom victory, Boies had grilled Bill Gates for twenty hours in a videotaped deposition that proved devastating to the software giant’s defense. He had gone on to represent Al Gore before the Supreme Court during the contested 2000 presidential election, cementing his status as a legal celebrity. More recently, he’d successfully led the charge to overturn Proposition 8, California’s ban on gay marriage.

12. Ian Gibbons

Highlight(yellow) - Location 2363

Inside Theranos, Ian’s death was handled with the same cold, businesslike approach. Most employees weren’t even informed of it. Elizabeth notified only a small group of company veterans in a brief email that made a vague mention of holding a memorial service for him. She never followed up and no service was held. Longtime colleagues of Ian’s like Anjali Laghari, a chemist who had worked closely with him for eight years at Theranos and for two years before that at another biotech company, were left guessing about what had happened. Most thought he had died of cancer. Tony Nugent became upset that nothing was done to honor his late colleague’s memory. He and Ian hadn’t been close. In fact, they had fought like cats and dogs at times during the Edison’s development. But he was bothered by the lack of empathy being shown toward someone who had contributed nearly a decade of his life to the company. It was as if working at Theranos was gradually stripping them all of their humanity. Determined to show he was still a human being with compassion for his fellow man, Tony downloaded a list of Ian’s patents from the patent office’s online database and cut and pasted them into an email. He embedded a photo of Ian above the list and sent the email around to the two dozen colleagues he could think of who had worked with him, making a point to copy Elizabeth. It wasn’t much, but it would at least give people something to remember him by, Tony thought.

13. Chiat\Day

Highlight(pink) - Location 2442

Chiat\Day was charging Theranos an annual retainer of $6 million a year. Where was this company nobody had heard of before getting the money to pay these types of fees? Elizabeth had stated on several occasions that the army was using her technology on the battlefield in Afghanistan and that it was saving soldiers’ lives. Stan wondered if Theranos was funded by the Pentagon.

Highlight(pink) - Location 2457

Elizabeth wanted the website and all the various marketing materials to feature bold, affirmative statements. One was that Theranos could run “over 800 tests” on a drop of blood. Another was that its technology was more accurate than traditional lab testing. She also wanted to say that Theranos test results were ready in less than thirty minutes and that its tests were “approved by FDA” and “endorsed by key medical centers” such as the Mayo Clinic and the University of California, San Francisco’s medical school, using the FDA, Mayo Clinic, and UCSF logos.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 2509

Elizabeth announced that Theranos’s legal team had ordered last-minute wording changes. Kate and Mike were annoyed. They’d been requesting a legal review for months. Why was it only happening now? The call dragged on for more than three hours until 10:30 p.m. They went over the site line by line, as Elizabeth slowly dictated every alteration that needed to be made. Patrick nodded off at one point. But Kate and Mike stayed alert enough to notice that the language was being systematically dialed back. “Welcome to a revolution in lab testing” was changed to “Welcome to Theranos.” “Faster results. Faster answers” became “Fast results. Fast answers.” “A tiny drop is all it takes” was now “A few drops is all it takes.” A blurb of text next to the photo of a blond-haired, blue-eyed toddler under the headline “Goodbye, big bad needle” had previously referred only to finger-stick draws. Now it read, “Instead of a huge needle, we can use a tiny finger stick or collect a micro-sample from a venous draw.” It wasn’t lost on Kate and Mike that this was tantamount to the disclaimer they had previously suggested. In a part of the site titled “Our Lab,” a banner running across the page beneath an enlarged photo of a nanotainer had stated, “At Theranos, we can perform all of our lab tests on a sample 1/₁,₀₀₀ the size of a typical blood draw.” In the new version of the banner, the words “all of” were gone. Lower down on the same page was the claim Kate had pushed back against months earlier. Under the heading “Unrivaled accuracy,” it cited the statistic about 93 percent of lab errors being caused by humans and inferred from it that “no other laboratory is more accurate than Theranos.” Sure enough, that was walked back too.

14. Going Live

Highlight(yellow) - Location 2582

BY THE SUMMER of 2013, as Chiat\Day scrambled to ready the Theranos website for the company’s commercial launch, the 4S, aka the miniLab, had been under development for more than two and a half years. But the device remained very much a work in progress. The list of its problems was lengthy. The biggest problem of all was the dysfunctional corporate culture in which it was being developed. Elizabeth and Sunny regarded anyone who raised a concern or an objection as a cynic and a naysayer. Employees who persisted in doing so were usually marginalized or fired, while sycophants were promoted. Sunny had elevated a group of ingratiating Indians to key positions. One of them was Sam Anekal, the manager in charge of integrating the various components of the miniLab who had clashed with Ian Gibbons. Another was Chinmay Pangarkar, a bioengineer with a Ph.D. in chemical engineering from the University of California, Santa Barbara. There was also Suraj Saksena, a clinical chemist who had a Ph.D. in biochemistry and biophysics from Texas A&M. On paper, all three had impressive educational credentials, but they shared two traits: they had very little industry experience, having joined the company not long after finishing their studies, and they had a habit of telling Elizabeth and Sunny what they wanted to hear, either out of fear or out of desire to advance, or both. For the dozens of Indians Theranos employed, the fear of being fired was more than just the dread of losing a paycheck. Most were on H-1B visas and dependent on their continued employment at the company to remain in the country. With a despotic boss like Sunny holding their fates in his hands, it was akin to indentured servitude. Sunny, in fact, had the master-servant mentality common among an older generation of Indian businessmen. Employees were his minions. He expected them to be at his disposal at all hours of the day or night and on weekends. He checked the security logs every morning to see when they badged in and out. Every evening, around seven thirty, he made a fly-by of the engineering department to make sure people were still at their desks working. With time, some employees grew less afraid of him and devised ways to manage him, as it dawned on them that they were dealing with an erratic man-child of limited intellect and an even more limited attention span. Arnav Khannah, a young mechanical engineer who worked on the miniLab, figured out a surefire way to get Sunny off his back: answer his emails with a reply longer than five hundred words. That usually bought him several weeks of peace because Sunny simply didn’t have the patience to read long emails.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 2613

Not all the setbacks encountered during the miniLab’s development could be laid at Sunny’s feet, however. Some were a consequence of Elizabeth’s unreasonable demands. For instance, she insisted that the miniLab cartridges remain a certain size but kept wanting to add more assays to them. Arnav didn’t see why the cartridges couldn’t grow by half an inch since consumers wouldn’t see them. After her run-in with Lieutenant Colonel David Shoemaker, Elizabeth had abandoned her plan of putting the Theranos devices in Walgreens stores and operating them remotely, to avoid problems with the FDA. Instead, blood pricked from patients’ fingers would be couriered to Theranos’s Palo Alto lab and tested there. But she remained stuck on the notion that the miniLab was a consumer device, like an iPhone or an iPad, and that its components needed to look small and pretty. She still nurtured the ambition of putting it in people’s homes someday, as she had promised early investors. Another difficulty stemmed from Elizabeth’s insistence that the miniLab be capable of performing the four major classes of blood tests: immunoassays, general chemistry assays, hematology assays, and assays that relied on the amplification of DNA.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 2643

Aside from its cartridge, pipette, and temperature issues, many of the other technical snafus that plagued the miniLab could be chalked up to the fact that it remained at a very early prototype stage. Less than three years was not a lot of time to design and perfect a complex medical device. These problems ranged from the robots’ arms landing in the wrong places, causing pipettes to break, to the spectrophotometers being badly misaligned. At one point, the blood-spinning centrifuge in one of the miniLabs blew up. These were all things that could be fixed, but it would take time. The company was still several years away from having a viable product that could be used on patients. However, as Elizabeth saw it, she didn’t have several years. Twelve months earlier, on June 5, 2012, she’d signed a new contract with Walgreens that committed Theranos to launching its blood-testing services in some of the pharmacy chain’s stores by February 1, 2013, in exchange for a $100 million “innovation fee” and an additional $40 million loan. Theranos had missed that deadline—another postponement in what from Walgreens’s perspective had been three years of delays. With Steve Burd’s retirement, the Safeway partnership was already falling apart, and if she waited much longer, Elizabeth risked losing Walgreens too. She was determined to launch in Walgreens stores by September, come hell or high water. Since the miniLab was in no state to be deployed, Elizabeth and Sunny decided to dust off the Edison and launch with the older device. That, in turn, led to another fateful decision—the decision to cheat.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 2719

She tried to talk sense into Elizabeth and Daniel Young by emailing them Edison data from Theranos’s last study with a pharmaceutical company—Celgene—which dated back to 2010. In that study, Theranos had used the Edison to track inflammatory markers in the blood of patients who had asthma. The data had shown an unacceptably high error rate, causing Celgene to end the companies’ collaboration. Nothing had changed since that failed study, Anjali reminded them. Neither Elizabeth nor Daniel acknowledged her email. After eight years at the company, Anjali felt she was at an ethical crossroads. To still be working out the kinks in the product was one thing when you were in R&D mode and testing blood volunteered by employees and their family members, but going live in Walgreens stores meant exposing the general population to what was essentially a big unauthorized research experiment. That was something she couldn’t live with. She decided to resign. When Elizabeth heard the news, she asked Anjali to come by her office. She wanted to know why she was leaving and whether she could be persuaded to stay. Anjali repeated her concerns: the Edison’s error rate was too high and the nanotainer still had problems. Why not wait until the 4S was ready? Why rush to launch now? she asked. “Because when I promise something to a customer, I deliver,” Elizabeth replied. That response made no sense to Anjali. Walgreens was just a business partner. Theranos’s ultimate customers would be the patients who came to Walgreens stores and ordered its blood tests thinking they could rely on them to make medical decisions. Those were the customers Elizabeth should be worrying about.

15. Unicorn

Highlight(yellow) - Location 2751

The brilliant young Stanford dropout behind the breakthrough invention was anointed “the next Steve Jobs or Bill Gates” by no less than former secretary of state George Shultz, the man many credited with winning the Cold War, in a quote at the end of the article. Elizabeth had engineered the piece, which was published in the Saturday, September 7, 2013, edition of the Journal, to coincide with the commercial launch of Theranos’s blood-testing services. A press release was due to go out first thing Monday morning announcing the opening of the first Theranos wellness center in a Walgreens store in Palo Alto and plans for a subsequent nationwide expansion of the partnership. For a heretofore unknown startup, coverage this flattering in one of the country’s most prominent and respected publications was a major coup. What had made it possible was Elizabeth’s close relationship with Shultz—a connection she’d made two years earlier and carefully cultivated.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 2772

Nor did Rago, who had won a Pulitzer Prize for tough editorials dissecting Obamacare, have any reason to suspect that what Elizabeth was telling him wasn’t true. During his visit to Palo Alto, she had shown him the miniLab and the six-blade side by side and he had volunteered for a demonstration, receiving what appeared to be accurate lab results in his email in-box before he even left the building. What he didn’t know was that Elizabeth was planning to use the Walgreens launch and his accompanying article containing her misleading claims as the public validation she needed to kick-start a new fund-raising campaign, one that would propel Theranos to the forefront of the Silicon Valley stage.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 2791

Don explained excitedly that Theranos had come a long way since then. The company was about to announce the launch of its innovative finger-stick tests in one of the country’s largest retail chains. And that wasn’t all, he said. The Theranos devices were also being used by the U.S. military. “Did you know they’re in the back of Humvees in Iraq?” he asked Mike. Mike wasn’t sure he’d heard right. “What?” he blurted out. “Yeah, I saw them stacked up at Theranos’s headquarters after they came back.” If all this was true, these were impressive developments, Mike thought. Don had launched a new firm in 2009 called the Lucas Venture Group. In recognition of her longstanding relationship with his aging father, who was addled by the onset of Alzheimer’s disease, Elizabeth was giving him the chance to invest in the company at a discount to the price other investors were going to be offered in a big forthcoming fund-raising round. Intent on seizing what he saw as a great opportunity, the Lucas Venture Group was raising money for two new funds, Don told Mike. One of them was a traditional venture fund that would invest in several companies, including Theranos. The second would be exclusively devoted to Theranos. Did Mike want in? If so, time was short. The transaction had to close by the end of September. A few weeks later, on the afternoon of September 9, 2013, Mike received an email from Don with the subject line “Theranos-time sensitive” that contained more details. The email, which went out to people who like Mike had previously invested in Don’s funds, provided links to the Wall Street Journal article and to the Theranos press release from that morning. The Lucas Venture Group, it said, had been “invited” to invest up to $15 million in Theranos. The discounted price Elizabeth was offering the firm valued the company at $6 billion.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 2809

It also said the company had been “cash flow positive since 2006.”

Highlight(pink) - Location 2852

Sunny also told James and Grossman that Theranos had developed about three hundred different blood tests, ranging from commonly ordered tests to measure glucose, electrolytes, and kidney function to more esoteric cancer-detection tests. He boasted that Theranos could perform 98 percent of them on tiny blood samples pricked from a finger and that, within six months, it would be able to do all of them that way. These three hundred tests represented 99 to 99.9 percent of all laboratory requests, and Theranos had submitted every single one of them to the FDA for approval, he said. Sunny and Elizabeth’s boldest claim was that the Theranos system was capable of running seventy different blood tests simultaneously on a single finger-stick sample and that it would soon be able to run even more. The ability to perform so many tests on just a drop or two of blood was something of a Holy Grail in the field of microfluidics. Thousands of researchers around the world in universities and industry had been pursuing this goal for more than two decades, ever since the Swiss scientist Andreas Manz had shown that the microfabrication techniques developed by the computer chip industry could be repurposed to make small channels that moved tiny volumes of fluids. But it had remained beyond reach for a few basic reasons. The main one was that different classes of blood tests required vastly different methods. Once you’d used your micro blood sample to perform an immunoassay, there usually wasn’t enough blood left for the completely different set of lab techniques a general chemistry or hematology assay required. Another was that, while microfluidic chips could handle very small volumes, no one had yet figured out how to avoid losing some of the sample during its transfer to the chip. Losing a little bit of the blood sample didn’t matter much when it was large, but it became a big problem when it was tiny. To hear Elizabeth and Sunny tell it, Theranos had solved these and other difficulties—challenges that had bedeviled an entire branch of bioengineering research.

Highlight(pink) - Location 2868

Besides Theranos’s supposed scientific accomplishments, what helped win James and Grossman over was its board of directors. In addition to Shultz and Mattis, it now included former secretary of state Henry Kissinger, former secretary of defense William Perry, former Senate Arms Services Committee chairman Sam Nunn, and former navy admiral Gary Roughead. These were men with sterling, larger-than-life reputations who gave Theranos a stamp of legitimacy. The common denominator between all of them was that, like Shultz, they were fellows at the Hoover Institution. After befriending Shultz, Elizabeth had methodically cultivated each one of them and offered them board seats in exchange for grants of stock. The presence of these former cabinet members, congressmen, and military officials on the board also lent credence to Elizabeth and Sunny’s assertions that Theranos’s devices were being used in the field by the U.S. military. James and Grossman thought that Theranos’s finger-stick offerings in Walgreens and Safeway stores were likely to be a hit with consumers and to capture a large share of the U.S. blood-testing market. A contract with the Department of Defense would add another big source of revenues.

Highlight(pink) - Location 2877

A spreadsheet with financial projections Sunny sent the hedge fund executives supported this notion. It forecast gross profits of $165 million on revenues of $261 million in 2014 and gross profits of $1.08 billion on revenues of $1.68 billion in 2015. Little did they know that Sunny had fabricated these numbers from whole cloth. Theranos hadn’t had a real chief financial officer since Elizabeth had fired Henry Mosley in 2006.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 2888

On February 4, 2014, Partner Fund purchased 5,655,294 Theranos shares at a price of $17 a share—$2 a share more than the Lucas Venture Group had paid just four months earlier. The investment brought in another $96 million to Theranos’s coffers and valued it at a stunning $9 billion. This meant that Elizabeth, who owned slightly more than half of the company, now had a net worth of almost $5 billion.

16. The Grandson

Highlight(yellow) - Location 2955

During the Thanksgiving holiday, a patient order came in from the Walgreens store in Palo Alto for a vitamin D test. As she had been trained to do, Erika ran a quality-control check on the Edison devices before testing the patient sample. Quality-control checks are a basic safeguard against inaccurate results and are at the heart of the way laboratories operate. They involve testing a sample of preserved blood plasma that has an already-known concentration of an analyte and seeing if the lab’s test for that analyte matches the known value. If the result obtained is two standard deviations higher or lower than the known value, the quality-control check is usually deemed to have failed. The first quality-control check Erika ran failed, so she ran a second one. That one failed too. Erika was unsure what to do. The lab’s higher-ups were on vacation, so she emailed an emergency help line the company had set up. Sam Anekal, Suraj Saksena, and Daniel Young responded to her email with various suggestions, but nothing they proposed worked. After a while, an employee named Uyen Do from the research-and-development side came down and took a look at the quality-control readings. Under the protocol Sunny and Daniel had established, the way Theranos generated a result from the Edisons was unorthodox to say the least. First, the little finger-stick samples were diluted with the Tecan liquid handler and split into three parts. Then the three diluted parts were tested on three different Edisons. Each device had two pipette tips that dropped down into the diluted blood, generating two values. So together, the three devices produced six values. The final result was obtained by taking the median of those six values. Following this protocol, Erika had tested two quality-control samples across three devices, generating six values during each run for a total of twelve values. Without bothering to explain her rationale to Erika, Do deleted two of those twelve values, declaring them outliers. She then went ahead and tested the patient sample and sent out a result. This wasn’t how you were supposed to handle repeat quality-control failures. Normally, two such failures in a row would have been cause to take the devices off-line and recalibrate them. Moreover, Do wasn’t even authorized to be in the clinical lab. Unlike Erika, she didn’t have a CLS license and had no standing to process patient samples. The episode left Erika shaken.

17. Fame

Highlight(yellow) - Location 3251

Leaving those quirks aside, what Elizabeth told Parloff she’d achieved seemed genuinely innovative and impressive. As she and Sunny had stated to Partner Fund, she told him the Theranos analyzer could perform as many as seventy different blood tests from one tiny finger-stick draw and she led him to believe that the more than two hundred tests on its menu were all finger-stick tests done with proprietary technology. Since he didn’t have the expertise to vet her scientific claims, Parloff interviewed the prominent members of her board of directors and effectively relied on them as character witnesses. He talked to Shultz, Perry, Kissinger, Nunn, Mattis, and to two new directors: Richard Kovacevich, the former CEO of the giant bank Wells Fargo, and former Senate majority leader Bill Frist. Before going into politics, Frist had been a heart and lung transplant surgeon. All of them vouched for Elizabeth emphatically. Shultz and Mattis were particularly effusive. “Everywhere you look with this young lady, there’s a purity of motivation,” Shultz told him. “I mean she really is trying to make the world better, and this is her way of doing it.” Mattis went out of his way to praise her integrity. “She has probably one of the most mature and well-honed sense of ethics—personal ethics, managerial ethics, business ethics, medical ethics that I’ve ever heard articulated,” the retired general gushed.

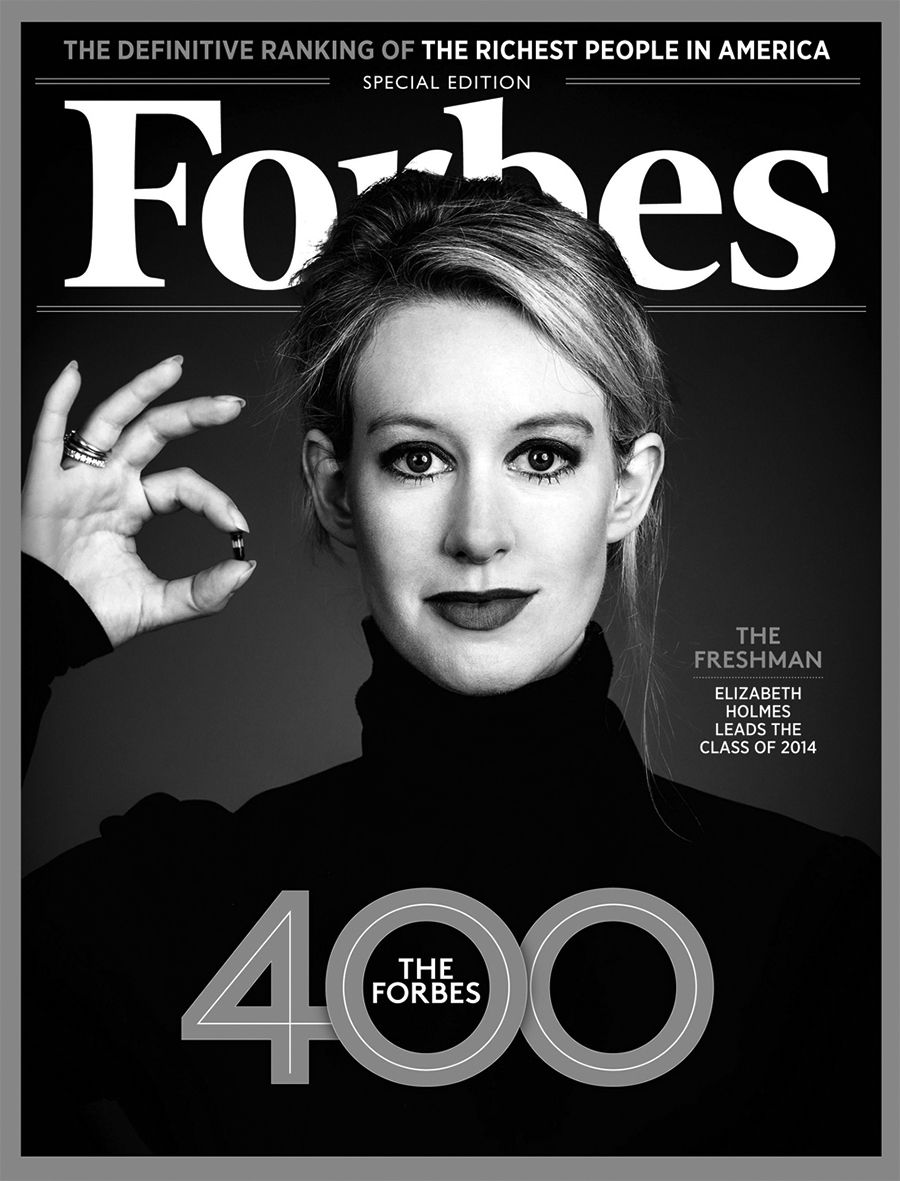

Highlight(yellow) - Location 3277

When the editors at Forbes saw the Fortune article, they immediately assigned reporters to confirm the company’s valuation and the size of Elizabeth’s ownership stake and ran a story about her in their next issue. Under the headline “Bloody Amazing,” the article pronounced her “the youngest woman to become a self-made billionaire.” Two months later, she graced one of the covers of the magazine’s annual Forbes 400 issue on the richest people in America. More fawning stories followed in USA Today, Inc., Fast Company, and Glamour, along with segments on NPR, Fox Business, CNBC, CNN, and CBS News. With the explosion of media coverage came invitations to numerous conferences and a cascade of accolades. Elizabeth became the youngest person to win the Horatio Alger Award. Time magazine named her one of the one hundred most influential people in the world. President Obama appointed her a U.S. ambassador for global entrepreneurship, and Harvard Medical School invited her to join its prestigious board of fellows. As much as she courted the attention, Elizabeth’s sudden fame wasn’t entirely her doing. Her emergence tapped into the public’s hunger to see a female entrepreneur break through in a technology world dominated by men. Women like Yahoo’s Marissa Mayer and Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg had achieved a measure of renown in Silicon Valley, but they hadn’t created their own companies from scratch. In Elizabeth Holmes, the Valley had its first female billionaire tech founder.

Highlight(pink) - Location 3300

In September 2014, three months after the Fortune cover story, she made that message more poignant during a speech at the TEDMED conference in San Francisco by adding a personal dimension to it: for the first time, she told the story in public of her uncle who had died of cancer—the same story Tyler Shultz had found so inspiring when he’d started working at Theranos. It was true that Elizabeth’s uncle, Ron Dietz, had died eighteen months earlier from skin cancer that had metastasized and spread to his brain. But what she omitted to disclose was that she had never been close to him. To family members who knew the reality of their relationship, using his death to promote her company felt phony and exploitative. Of course, no one in the audience at San Francisco’s Palace of Fine Arts knew this. Most of the one thousand spectators in attendance found her performance mesmerizing.

18. The Hippocratic Oath

Highlight(pink) - Location 3365

He now felt like a pawn in a dangerous game being played with patients, investors, and regulators. At one point, he’d had to talk Sunny and Elizabeth out of running HIV tests on diluted finger-stick samples. Unreliable potassium and cholesterol results were bad enough. False HIV results would have been disastrous. His codirector, Mark Pandori, had quit after just five months on the job. The trigger had been a request he’d made that Elizabeth check in with them before making representations to the press about Theranos’s testing capabilities. Sunny had summarily rejected it, prompting Mark to hand in his resignation that very day.

Highlight(yellow) - Location 3452

in its December 15, 2014, issue, The New Yorker published a profile of Elizabeth. In many ways, it was just a longer version of the Fortune story that had rocketed her to fame six months earlier. The difference this time was that someone knowledgeable about blood testing read it and was immediately dubious. That someone was Adam Clapper, a practicing pathologist in Columbia, Missouri, who in his spare time wrote a blog about the industry called Pathology Blawg. To Clapper, it all sounded too good to be true, especially Theranos’s supposed ability to run dozens of tests on just a drop of blood pricked from a finger. The New Yorker article did strike some skeptical notes. It included quotes from a senior scientist at Quest who said he didn’t think finger-stick blood tests could be reliable, and it noted Theranos’s lack of published, peer-reviewed data. Among the arguments she marshaled to rebut the latter point, Elizabeth cited a paper she had coauthored in a medical journal called Hematology Reports. Clapper had never heard of Hematology Reports before, so he looked into it. He learned that it was an online-only publication based in Italy that charged scientists who wanted to publish in it a five-hundred-dollar fee. He then looked up the paper Holmes had coauthored and was shocked to see that it included data for just one blood test from a grand total of six patients. In a post on his blog about the New Yorker story, Clapper pointed out the medical journal’s obscurity and the flimsiness of the study and declared himself a skeptic “until I see evidence Theranos can deliver what it says it can deliver in terms of diagnostic accuracy.”

19. The Tip

Highlight(yellow) - Location 3517

When I stopped to think about it, I found it hard to believe that a college dropout with just two semesters of chemical engineering courses under her belt had pioneered cutting-edge new science. Sure, Mark Zuckerberg had learned to code on his father’s computer when he was ten, but medicine was different: it wasn’t something you could teach yourself in the basement of your house.

Bookmark - Location 3675

21. Trade Secrets

Highlight(yellow) - Location 4030

Far from backing off, Theranos stepped it up a notch. Later that week, Boies sent the Journal a second letter. Unlike the first one, which was just two pages long, this one ran twenty-three pages and explicitly threatened a lawsuit if we published a story that defamed Theranos or disclosed any of its trade secrets. Much of the letter was a searing assault on my journalistic integrity. In the course of my reporting, I had “fallen far short of being fair, objective, or impartial” and instead appeared hell-bent on “producing a predetermined (and false) narrative,” Boies wrote. His main evidence to back up that argument was signed statements Theranos had obtained from two of the other doctors I had spoken to claiming I had mischaracterized what they had told me and hadn’t made clear to them that I might use the information in a published article. The doctors were Lauren Beardsley and Saman Rezaie from the Scottsdale practice I’d visited. The truth was that I hadn’t planned on using the patient case Drs. Beardsley and Rezaie had told me about because it was a secondhand account. The patient in question was being treated by another doctor in their practice who had declined to speak to me. But, while their signed statements in no way weakened my story, the likelihood that they had caved to the company’s pressure worried me. I noticed there was no signed statement from Adrienne Stewart, the third doctor I had interviewed at that practice. That was a good thing because I planned on using one or both of the patient cases she had discussed with me. When I reached her by phone, she said that she was visiting family in Indiana and hadn’t been present when Theranos representatives came by the practice. I told her about her colleagues’ signed statements and warned her that the company would probably try the same heavy-handed tactics with her when she returned. Dr. Stewart emailed a few days later to let me know that Balwani and two other men had indeed come by to speak to her as soon as she’d gotten back to Arizona. The receptionist had told them she was busy with patients, but they had refused to leave and had stayed in the waiting room for hours until she finally came out to shake their hands. They had made her agree to meet with them the following Friday morning, which was in two days. I had a bad feeling about that meeting, but there was nothing I could do about it. Dr. Stewart promised she wouldn’t bow to any pressure. She felt it was important to take a stand for her patients and the integrity of lab testing. When Friday arrived, I tried to check in with Dr. Stewart several times in the morning but couldn’t reach her. She called back in the early evening, as I was driving out to eastern Long Island for the weekend with my wife and three kids. She sounded rattled. She told me Balwani had tried to make her sign a statement similar to the one her colleagues had signed, but she had politely refused. Furious, he had threatened to drag her reputation through the mud if she appeared in any Journal article about Theranos. Her voice trembling, she pleaded with me to no longer use her name. As I tried to reassure her that it was an empty threat, it dawned on me that there was nothing these people would stop at to make my story go away.

22. La Mattanza

Highlight(pink) - Location 4097

The tests’ progress was represented by the darkening edge of a circle on the devices’ digital screens, like app downloads on an iPhone. Inside the circle, a percentage number told the user how much of the test had been completed. Based on how slowly the edge of one of the circles was filling up, it looked to Parloff like it might take several more hours. He couldn’t wait around that long. He told Edlin he needed to head back to work. After Parloff left, Kyle Logan, the young chemical engineer who had won an academic award at Stanford named after Channing Robertson, entered the conference room. He’d flown in with Edlin on the red-eye from San Francisco that morning and was there to provide technical support. Noticing that the miniLab running the potassium test was stuck at 70 percent completion, he took the cartridge out and rebooted the machine. He had a pretty good idea what had happened. Balwani had tasked a Theranos software engineer named Michael Craig to write an application for the miniLab’s software that masked test malfunctions. When something went wrong inside the machine, the app kicked in and prevented an error message from appearing on the digital display. Instead, the screen showed the test’s progress slowing to a crawl. This is exactly what had happened with Parloff’s potassium test. Luckily, enough of the test had occurred before the malfunction that Kyle was able to retrieve a result from the machine. The breakdown had happened while the device was running the test again on the control part of the sample. Normally, it would have been preferable to have the initial result confirmed by the control, but Daniel Young told Kyle over the phone that it was OK to do without it in this case. In the absence of real validation data, Holmes used these demos to convince board members, prospective investors, and journalists that the miniLab was a finished, working product. Michael Craig’s app wasn’t the only subterfuge used to maintain the illusion. During demos at headquarters, employees would make a show of placing the finger-stick sample of a visiting VIP in the miniLab, wait until the visitor had left the room, and then take the sample out and bring it to a lab associate, who would run it on one of the modified commercial analyzers. As for Parloff, he had no idea he’d been duped. That evening, he got an email from Theranos with a password-protected attachment containing his results. When he opened the attachment, he was happy to see that he’d tested negative for Ebola and that his potassium value was within the normal range.

Highlight(pink) - Location 4117

BACK IN CALIFORNIA, Holmes and Balwani were laying the groundwork for a bigger show-and-tell. Holmes had invited Vice President Joe Biden to come visit Theranos’s Newark facility, which was now home to both Theranos’s clinical laboratory and its miniLab manufacturing operations. It was an audacious move given that, since Alan Beam’s departure in December 2014, the lab had been operating without a real director. To keep this hidden, Balwani had recruited a dermatologist named Sunil Dhawan to replace Beam on the lab’s CLIA license. Although Dhawan had no degree or board certification in pathology, he technically met state and federal requirements because he was a medical doctor and had overseen a little lab affiliated with his dermatology practice that analyzed skin samples. The reality, however, was that he was unqualified to run a full-fledged clinical lab. Not that it mattered. Balwani only intended him to be a figurehead. Some lab employees in Newark never saw Dhawan in the building.

Highlight(pink) - Location 4125

Two months earlier, Balwani had terrorized its members after a scathing critique of Theranos appeared on Glassdoor, the website where current and former employees reviewed companies anonymously. Titled “A pile of PR lies,” it read in part: Super high turnover rate means you’re never bored at work. Also good if you’re an introvert because each shift is short-staffed. Especially if you’re swing or graveyard. You essentially don’t exist to the company. Why be bothered with lab coats and safety goggles? You don’t need to use PPE at all. Who cares if you catch something like HIV or Syphilis? This company sure doesn’t! Brown nosing, or having a brown nose, will get you far. How to make money at Theranos: 1. Lie to venture capitalists 2. Lie to doctors, patients, FDA, CDC, government. While also committing highly unethical and immoral (and possibly illegal) acts. Negative Glassdoor reviews about the company weren’t unusual. Balwani made sure they were balanced out by a steady flow of fake positive reviews he ordered members of the HR department to write. But this particular one had sent him into a rage. After getting Glassdoor to remove it, he’d launched a witch hunt in Newark, conducting interrogations of employees he suspected of having written it. He was so mean to one of them, a woman named Brooke Bivens, that he made her cry. He never found the culprit.

Highlight(pink) - Location 4147