Utopia For Realists

Read this book. It's short, accessible, and yet extremely powerful. It'll make you hate bankers, appreciate large governments, and develop a strong, practical aversion to anything remotely xenophobic. Bregman writes clear, evidence-backed chapters that naturally lead into each other thematically, prose that flow smoothly in broad arcs. Utopia For Realists will certainly challenge you to confront your beliefs thanks to the powerful arguments it present for (i) giving money to the poor to eradicate poverty, (ii) implementing a universal basic income (especially in the face of rising automation) while reducing the average work-week,(iii) punishing bankers and rewarding garbage collectors (somehow) via realizing that salary =/= societal value, (iv) opening up borders and fixing development aid, and (v) understanding that bigger government = a good.

(i) Domestic Poverty

[This TED talk by Bregman entitled 'Poverty isn't a lack of character, it's a lack of cash' offers a good exploration of the subject / argument that is repeated in his book]

"Poverty is fundamentally about a lack of cash," says economist Joseph Hanlon who Bregman presciently quotes. "It's not about stupidity." Despite this, the idea of giving money away (especially taxpayer money) to the poor disturbs most people to the core. It feels fundamentally unjust and makes one wonder why should they should have to work if others get a free ride -- economists wrap this in a more elaborate argument about labor market incentives.

Bregman counters the above argument, often politicized and indoctrinated, with evidence. In 2009, London's thirteen most expensive homeless men, who racked up annual bills of $650,000, were given $4500 each with no strings attached. 18 months later, seven of them had a roof over their heads, and the total program had cost only $81000.

Why? It's right (google 'the veil of ignorance') and cost effective

(ii)a Implement a Universal Basic Income (UBI)

Although Switzerland had a referendum (failed 23-76) on the matter recently in 2016, the UBI lacks popular support today. It's crazy to think, however, that in 1967 almost 80% of Americans supported a guaranteed basic income, and it nearly became law when President Nixon's Family Assistance Plan resoundingly passed the House of Representatives 243-155 (it later was rejected in the Senate).

It's less crazy to imagine how politically charged the concept of a UBI is. Bregman fascinatingly raises the hypothesis that Nixon backpedaled on his firm commitment to a UBI after his political advisor Martin Anderson, a firm Ayn Rand believer, showed him the historical record of Speenhamland, a case-study (that also supposedly inspired Das Kapital) conducted by a Royal Commission from 19th century England that exemplified the 'lazy poor'.

However, future secondary studies of the original report revealed that it was flawed: of the questionnaires distributed, only 10% were ever filled out. Further, they were mostly filled by the local elite whose general view was that the poor were only growing more wicked and lazy. The consequences in England of the Speenhamland case were immediate and drastic: the portion of GDP spent on poor relief was halved (2% to 1%) and new Poor Laws were drafted that made almshouses mandatory for the needy. FYI: almshouses were like the work mill settings of Oliver Twist, essentially extremely cheap, over-exploited labor for the already-rich.

Why? It'll be necessary when only 50% of us work 20 hour workweeks because of AI. Better to pilot / develop it now than when necessary as a panicked response to a crisis.

(ii)b Reduce the Workweek

In the mid-1960s, a Senate committee report projected that by 2000, the workweek would be reduced to fourteen hours with at least seven weeks off a year (that would be nice). This obviously seems fanciful to us today, but back then the downward historical trajectory of the average workweek made it not only seem plausible, but likely: in the US, 40 hour workweeks were achieved in ~1950, down from 60 in ~1850.

Working more doesn't necessarily more useful output: productivity experts calculated that had Apple employees worked half the hours they had they might have invented the Macintosh computer a year earlier. (Maynard et al., "Empowerment - Fad or Fab? A Multilevel Review of the Past Two Decades of Research", 2012)

Why? It's practical: it doesn't make sense to work more, get less, and encourage burnout. Also, we need to start exploring what we'll do with our inevitable increasing leisure time. Bregman also hints that work is slowly becoming reserved for the rich (think of the long hours of investment bankers and lawyers).

(iii) Understand that Salary =/= Societal Value

"The genius of the great speculative investors is to see what others do not, or to see it earlier. This is a skill. But so is the ability to stand on tiptop, balancing on one leg, while holding a pot of tea above your head, without spillage." Roger Bootle

As Bregman perfectly puts into words:

"It has become increasingly profitable not to innovate. Imagine just how much progress we've missed out on because thousands of bright minds have frittered away their time dreaming up hyper complex financial products that are ultimately only destructive. Or spent the best years of their lives duplicating existing pharmaceuticals in a way that's infinitesimally different enough to warrant a new patent application by a brainy lawyer so a brilliant PR department can launch a brand-new marketing campaign for the not-so-brand-new drug.

Imagine that all this talent were to be invested not in shifting wealth around, but in creating it… Maybe a fat billfold triggers a … false consciousness: the conviction that you're producing something of great value because you earn so much."

Martin Shkreli touched a communal nerve when it became known that the pharma company he founded and operated, made money by buying manufacturing licenses of drugs and subsequently raising the drugs' prices by an order of magnitude -- in the case of Daraprim by 56. Although what Shkreli did was despicable (pricing many people out of the drugs they needed), what's even more shocking is how commonplace the practice is in the industry at-large, and further, how it's justified with layers of excuses obfuscated by economic and business jargon.

Capitalist societies vault the rich to the highest rungs of society. This is crowding out talent from the places we really need it; case in point, consider the defensive hiring measures of large tech companies -- link.

Why? Because it encourages smart people to go into industries that don't contribute to society.

(iv)a Open Borders

Immigrants =/= criminals. A 2004 Dutch study exploring the criminality of Moroccan immigrants in the Netherlands found that there was no correlation between ethnic background and crime. It turned out that youth crime had its origins in the neighborhoods were the kids grew up. Subsequent studies corroborated this. In fact, the Dutch researchers wrote recently that "asylum-immigrants are actually underrepresented relative to the native population." (link in Dutch, 2015)

They're also not lazy. In country's like Austria, Ireland, Spain, and England, they bring in more tax revenue per capita than the native population. This statement is extrapolated from the below data taken from the 2013 OEDC International Migration Outlook report, (p. 147, link)... any country where the blue bar sits higher than the white diamond indicates that immigrants contribute more... it's interesting to note how in almost every case, mixed households contribute the most.

Borders are upsetting because they also create immediately visceral ingroups and outgroups (link) which make a 30% domestic wage gap highly relevant but a 8500% international wage gap (between the US and Nigeria) irrelevant. They prioritise local politics over international politics because of almost-random lines drawn hundreds of years ago.

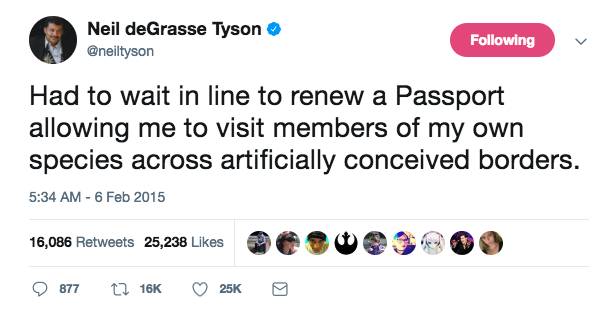

also, when it comes to the idea of borders, this tweet from Neil deGrasse Tyson really hits the nail on the head

Why? Plz

(iv)b Fix Development Aid

Esther Duflo, an MIT professor likened previous research on development aid to medieval bloodletting, the practice where the bodily humors of ill patients were rebalanced with leeches. If the patient died, it was God's will, and if he survived it was thanks to the skill of the physician. Essentially, it was completely smoke and mirrors. In 2003, she founded MIT's Poverty Action Lab which has now conducted over 500 studies in 56 countries.

Her analogy has merit because the first randomized controlled trial (you know, splitting your sample into A/B and giving your treatment to A, basic stuff) of foreign development aid didn't happen until 1998, when it was discovered that giving free text books to Kenyan grade-school pupils had no effects on their scores.

It turns out actually that $100 worth of free meals -> 2.8 additional years of educational attainment (3x as effective free uniforms), and deworming children (a $10 process) with intestinal complaints -> 2.9 years

It also happens that poor countries lose three times as much money to tax evasion than they receive in foreign aid (link, Guardian article written by ex-Sec Gen of the OEDC)... it's also known that foreign aid is often contingent on privatization of assets and liberalisation of markets -- things which end up usually stunting the developing nations growth. For more on this latter subject read Kicking Away the Ladder by Ha-Joon Chang (Amazon link).

Why? Because it's often ineffective and detrimental in the long-term.

(v) Appreciate a larger government

The portion of GDP apportioned to pay government employees is often connected to market inefficiencies. Yet, 'Baumol's cost disease' essentially predicts this to be inevitable with rising automation because the prices in labor-intensive sectors (government) increase faster than prices in sectors where work can be automated (duh, automation is cheap). But why is that necessarily a bad thing? As Bregman points out, isn't it a good thing that we have more time and resources to attend to the old and amend education? According to Baumol himself (a twentieth century economist), the only thing stopping us from allocating our resources in such a manner is "The illusion that we cannot afford them."

Why? It's a sign of our progress as a society; thank you technology that we don't all have to be farmers

Misc. findings

Poverty creates a scarcity mentality that has a cognitive cost

The average American thinks their federal government spends more than a quarter of the national budget on foreign aid, but the real figure is less than 1%

Quotes

Capitalist or communist, it all boils down to a pointless distinction between two types of poor, and to a major misconception that we almost managed to dispel some forty years ago -- the fallacy that a life without poverty is a privilege you have to work for, rather than a right we all deserve. (p 97)

If Ivy League grads once went on to jobs in science, public service, and education, these days they're far more likely to opt for banking, law, or ad proliferators like Google and Facebook. Stop for a moment to ponder the billions of tax dollars being pumped into training society's best brains, all so they can learn how to exploit other people as efficiently as possible, and it makes your head spin. Imagine how different things might be if our generation's best and brightest were to double down on the greatest challenges of our time. Climate change, for example, and the aging population, and inequality… Now that would be real innovation.